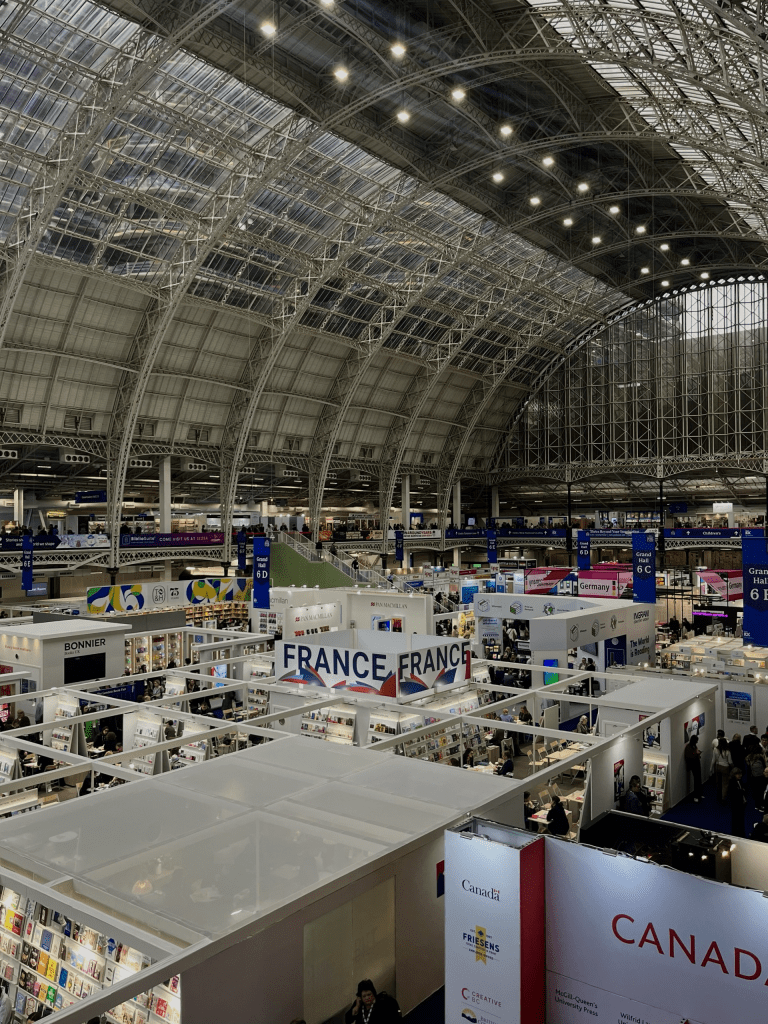

This year’s London Book Fair kicked-off with important conversations and extraordinary guest panelists, with industry experts giving us the full scope of everything publishing-related and catching up on all the current trends such as the ongoing tendency to read books in English across non-English speaking countries in Europe.

Growing up in Spain in an English-speaking household, I always struggled with reading books in Spanish (despite my father’s concerns of me losing my proficiency in the language, as if he had forgotten that I actually lived in Spain too). Not because I didn’t like the language, but simply because the books I read in Spanish were translations of books originally written by English-speaking authors and, when I picked up a translation, I found the writing to be missing something, it was just not the same as reading books in their original language. Because of this, I gradually stopped reading books in Spanish altogether (besides the occasional Spanish author, of course). And as it turns out, I’m not the only one who feels this way.

On 12 March, London Book Fair welcomed David Graham, managing director of BT Batsford and chair of the IPG, Geneviève Waldmann, CEO of Veen Bosch & Keuning (VBK), and Rebecca Servadio of London Literary Scouting to discuss the rise of English language book sales in Europe. As it turns out, lots of people prefer reading books in English. It was to my surprise to find out that English language book sales had increased in Spain by 30% to £67m in 2023, in contrast with 2022, with sales up to £51m. It’s great that people are reading in foreign languages, but, what does this mean for translations? Because these books are all imported from the UK or elsewhere, Spanish publishers who are putting out their own translations are struggling to find a selling-point for the market which, unsurprisingly, is mainly young readers. Why? Well, besides the current influence of (especially) American pop culture, translations are simply too expensive. Because of this, Waldmann explained that they have resorted to publishing the translation of English books with the exact same cover as the original version, in order to attract those readers who are gravitating towards the English one. She points out that, if the numbers keep increasing, ‘in five to ten years there will be no translations any more because we can’t afford it’. Not only is this bad for these countries’ own publishing industries, but it directly affects translators as well.

So, what’s the solution? Waldman gave a pretty good one (and one which created buzz among the room, might I add), which consisted of publishers putting out their own English version of the books instead of importing them from the US/UK, as well as offering their own translations of the titles. And while this could be a remedy to alleviate the stress over locally-published sales dropping, it is still quite an expensive one.

This was quite an eye-opening panel and one I discussed with my fellow peers and friends back home who also contribute to the increase of English-language book sales, and while reaching a conclusion is quite difficult, I will finish with the words of Servadio, who said ‘There needs to be a conversation about why should English dominate. Do you want to live in a mono-culture? It’s depressing’. While I agree with her statement and believe we should support our translators and local publishers, I believe the issue is rooted outside of publishing, for English dominance is everywhere, from the movies we watch, to the music we listen to, to what we see on social media (especially TikTok), every day. Publishers must then do what they do best, adapt to change, listen to their readers, and embrace the future generation of readers with open-mindedness.